Chris Kaiser | School of Science

May 22, 2018

This story was originally published on the MIT School of Science.

The rise of the information age in the second half of the 20th century was spurred on by two related but distinct scientific and technological revolutions. The first, of course, was the digital revolution, which emerged with the development of the mathematics necessary for computation and data storage based entirely on a binary code. The second revolution came about from the discovery that information encoded in the molecular sequence of DNA carries the instructions for the working parts of a cell and thus is the blueprint of life. The field of molecular biology emerged as the study of how genetic information is transmitted from one generation to another and is read out to form functional cellular components and regulatory circuits.

The foundational science of molecular biology has led to methods for reading and writing biological information and to alter genomes by design. The capability to reprogram living organisms to do useful things forms the basis of the biotechnology industry.

No single institution has had a greater impact in accelerating the revolution in molecular biology and biotechnology than MIT. The origins of this revolution is woven deeply into the history of the Department of Biology.

MIT’s revolutionary foundation

In the late 1950s, MIT’s administration began a deliberate and concerted effort to recruit molecular biologists even before this nascent research area was recognized as a distinct field that would transform all of biology. The decision was made to hire faculty who were interested in studying biology by uncovering relationships between molecular structure and function and understanding the biochemical basis of genetic information and the transmission of genetic traits.

At the University of Wisconsin, Gobind Khorana celebrates his 1968 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine awarded for his contributions to elucidation of the genetic code. Even at this celebration, he was already looking forward to the next experiments. Here, he explains the strategy for enzymatic gene synthesis using diagrams of hybridizing strands. Photo: Tom RajBhandary.

One such seminal hire was Alex Rich, the William Thompson Sedgwick Professor of Biophysics, who came to MIT in 1958. Rich contributed to the discovery of how single strands of DNA and RNA molecules can find and match complementary sequences. This process, called nucleic acid hybridization, remains one of the fundamental methods for reading out the identity of nucleic acid molecules. In addition to foundational research into hybridization, Rich also elucidated the three-dimensional structure of the transfer RNA molecule that functions in reading the genetic code.

A second enormously influential hire was Salvador Luria who moved from the University of Illinois to MIT in 1959. Luria was a leader in the study of bacteriophages — viruses that infect bacterial cells. Much in the same way that early quantum physicists used the hydrogen atom to establish a theory for quantum structure of atoms, the first molecular geneticists used the bacteriophage as a simple genetic system to reveal the rules for fundamental genetic processes such as replication, recombination, and mutation.

By the 1960s, the understanding of fundamental genetic mechanisms developed by Luria and others had merged with the work of structural biologists such as Rich to give the outline of how genetic information was stored, copied, and read.

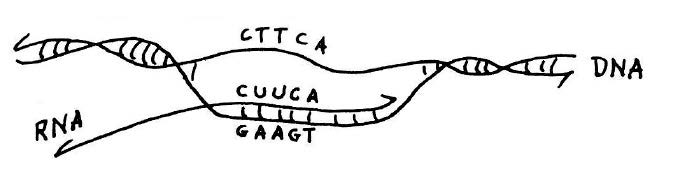

The reading of genetic information takes place in two steps. In the first step, known as transcription, genetic information encoded in DNA is used as a template to make a copy in the form of a single-stranded messenger RNA. In the second step, the information contained within the messenger RNA is translated into a protein sequence at the site of protein synthesis — the ribosome. Transfer RNA molecules serve as the key adaptor molecules that allow translation of messenger RNA sequences into the amino acid sequences of proteins. Each transfer RNA carries a triplet of nucleotides that pairs with and thus “reads” a specific three-nucleotide sequence along the messenger RNA. At its other end, the transfer RNA carries a particular amino acid that is added in its place in the sequence of the elongating protein chain.

Khorana cracks the code

Before Har Gobind Khorana arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1970, he worked with the great nucleotide chemist, Alexander Todd at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. Khorana was in the lab at the time that chemists were working out structure of the nucleotide building blocks of DNA and RNA. When Khorana started his own lab, first at University of British Columbia and then at University of Wisconsin, his work was devoted to using synthetic chemistry to make biologically important molecules and ever more complicated polynucleotide structures.

Khorana made one of the most consequential advances in molecular biology by using a hybrid approach that employed organic chemistry to synthesize short sequence of a few nucleotides followed by the use of a copying enzyme to generate long DNA molecules with many repeating copies of the short sequence. Khorana’s molecules with a repeating sequence were the keys to cracking the genetic code. A few years earlier, the complex process of translation was reconstituted in the test tube and was dependent on messenger RNA added from the outside. By using synthetic messenger RNAs to instruct the synthesis of proteins by the ribosome, Khorana’s group was able to work out rules for how specific sequences of three nucleotides in RNA are translated into the 20 possible amino acids. We now know that all forms of life use the same genetic code to read the information written in DNA. For his contributions to understanding the code, Khorana shared the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.

Synthesizing genes

As work on the code was nearing completion, Khorana began thinking about how to synthesize long polynucleotide molecules of even greater complexity. He had his eye on what could be considered a moonshot challenge in nucleic acid synthesis: to synthesize a functional gene.

Before an artificial gene could be synthesized, it was necessary, of course, to know the DNA sequence of the desired gene. In the mid-1960s, the ability to directly determine the DNA sequence of a protein-coding gene was still about a decade away; however, the DNA sequence of an RNA-coding gene could be deduced directly from the RNA sequence. The first complete sequence of a natural gene-encoded RNA molecule — the transfer RNA for the amino acid alanine — was determined by Robert Holley in 1965. In that year, Khorana began to organize his lab to synthesize the double-stranded DNA that would code for alanine transfer RNA. Although Khorana knew that this monumental task would require a combined and concerted effort of perhaps a decade of work, he expressed utter clarity and confidence in the purpose and significance of this endeavor.

In a review letter for the Biochemical Journal in 1968, he wrote: We would like to know, for example, what the initiation and termination signals for RNA polymerase are, what kind of sequences are recognized by repressors, by host modification and host restrictive enzymes, and by enzymes involved in genetic recombination, and so on. For these studies, ultimately what is required is the ability to synthesize long chains of DNA with specific non-repeating sequences. With this should come the ability to ‘manipulate’ DNA for different types of studies.

This description pretty well summarizes the work of a major segment of molecular biology for the next 50 years.

Copying of genetic information in DNA into RNA.Transcription is catalyzed by the enzyme RNA polymerase (not shown). This diagram shows that if the sequence of the RNA transcript is known, as was the case for alanine transfer RNA, the DNA sequence of the corresponding gene for the transfer RNA can be deduced from the rules of base pairing. This and figure below from he published lecture notes of Professor Salvador Luria who taught general biology (7.01) at MIT for many years. Credit: MIT Press, 1975, “36 Lectures in Biology.”

In theory, the DNA for alanine transfer RNA could be formed by synthesizing each complementary strand separately and then using hybridization to form a complete double-stranded helix. This approach would require synthesis of DNA strands that were 77 nucleotides long; however, at the time the upper limit for synthesis, even in Khorana’s laboratory, was about 20. The plan as originally conceived was to take advantage of the ability of DNA polymerase to synthesize DNA from a template. The idea was to synthesize oligo-nucleotides that partly overlapped and then to use DNA polymerase to complete a fully double-stranded DNA molecule. Khorana’s team started the synthesis of the gene for alanine transfer RNA in this way and showed that basic strategy of using chemical synthesis followed by synthesis by polymerase would work. But when the DNA ligase enzyme was discovered, it became more practical to chemically synthesize many short overlapping segments and stitch them together with ligase. In this manner, the synthesis of alanine transfer RNA gene was completed in 1970.

The first synthetic gene was in itself a monumental landmark in the progression of molecular biology; but like any successful moonshot, the technological innovations developed along the way may have had the furthest-reaching impact.

Knock-on effects

Marvin Caruthers joined Khorana part of the team synthesizing the alanine transfer RNA in 1966 and then came with him to MIT. Caruthers then went to the University of Colorado at Boulder, where he began his own research program developing methods for reliable automated synthesis of short DNA molecules, or oligonucleotides. He decided to carry out nucleotide synthesis on a solid support, which would greatly simplify and speed up the separation of the growing oligo-nucleotide chain away from precursor molecules as the process stepped through the reaction cycle for the addition of each base in the sequence.

Khorana had the vision and leadership to convince a team to follow him to an unknown place, and he had the supreme confidence that he would know what to do once he got there.

A second key innovation was Caruther’s development of nucleotide precursors that could be stored for long periods and then readily activated immediately before use. The so called “phosphoramidite method” for DNA synthesis was automated and its use enables scientists who are not expert organic chemists to synthesize their own oligonucleotides. The ready availability of oligonucleotide primers has driven the expansion of methods for reading DNA by sequencing and the copying and modification of DNA sequences at will. These technologies are analogous to the fundamental output and input devices of a digital computer but for the manipulation of biological information encoded in DNA.

The development of the by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is another key technological advance that stemmed from Khorana’s work. PCR employs the same basic elements proposed by Khorana for the synthesis of the alanine transfer RNA gene; hybridization of synthetic oligonucleotides to a target DNA followed by synthesis with DNA polymerase to produce double-stranded DNA of defined sequence. The key innovation as proposed by Kary Mullis when he came up with the idea for PCR was to use the same synthetic oligonucleotides to conduct many cycles of hybridization and synthesis. Because of the doubling that results from each round of replication, 20 cycles would give a million-fold amplification allowing a specific sequence to be produced from an extremely complex mixture such as a whole genome.

Twelve years before the invention of PCR, Khorana’s group showed that oligonucleotides defining the ends of the completed transfer RNA gene segment could be used to carry out rounds of hybridization and DNA synthesis with polymerase to make more of the desired DNA product without any additional labor in chemical synthesis of DNA. This raises the question of whether Khorana, who was a visionary, foresaw the possible application of his method for the amplification of sequences from whole genomes. It is worth pointing out that at the time Khorana’s group was contemplating enzymatic amplification, their synthetic gene was one of the only DNA sequences that was known and therefore a basic ingredient of the PCR method — knowledge of enough of an interesting target sequence to design the oligonucleotide primers for its amplification — was not available to them. Years later, when PCR patents were under litigation, the question of prior art arose; but Khorana refrained from comment, having moved on to the study of the light-sensing protein rhodopsin.

Visions for the next revolution

At a memorial service for Khorana held at MIT in 2012, many stories were told about his intellectual independence and visionary leadership in basic research that had far-reaching implications.

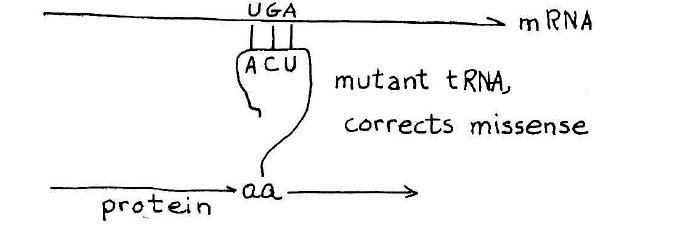

How a suppressor transfer RNA works. A stop codon introduced in the middle of a gene will cause premature termination of the protein chain. A suppressor transfer RNA has been altered so that it can read past a stop mutation suppress its effect. This provides a definitive genetic demonstration for functionality of a suppressor transfer RNA gene. Credit: MIT Press, 1975, “36 Lectures in Biology.”

As the synthesis of alanine transfer RNA gene was well underway, Khorana initiated a project reaching for an even bigger prize — a synthetic gene that could be shown to carry out its biological function in the context of a living cell. The candidate, known as a suppressor transfer RNA, was a recently sequenced transfer RNA that had the ability to read past a stop mutation introduced in the middle of a gene, thereby suppressing the effect of the mutation and allowing ribosomes to read the RNA and produce the protein. The idea that Khorana laid out for the team was to synthesize the suppressor transfer RNA and then introduce the synthetic gene into a suitable bacterial host designed to test its ability to suppress a stop mutation.

At that time, now standard methods for gene cloning and expression did not exist. As the planning moved forward, the team synthesizing the suppressor transfer RNA began to envision more and more elaborate schemes to get a functional suppressor transfer RNA gene into cells. As Caruthers related the story, Khorana listened quietly to the brainstorming for a bit and then said, “Let’s first synthesize the gene. By that time, we will know how to express it.” Khorana was right; and by the time the synthetic suppressor gene was complete, methods were available for introducing the gene into cells.

Like the great explorers Frances Drake and Ernest Shackleton who were my heroes growing up, Khorana had the vision and leadership to convince a team to follow him to an unknown place, and he had the supreme confidence that he would know what to do once he got there.

Transformational scientific and technological revolutions, like those initiated by Khorana, Luria, and Rich, are of keen interest because they help us understand the sparks of genius and originality that we should be looking for when we hire new faculty and illustrate the kinds of research projects in our institutions and companies that might lead to fundamental advances in preparation for the next scientific revolution.

Chris Kaiser is the Amgen Inc. Professor of Biology and the former head of the MIT Department of Biology.